OSE Derivatives

Platinum-for-palladium substitution

Executive Summary

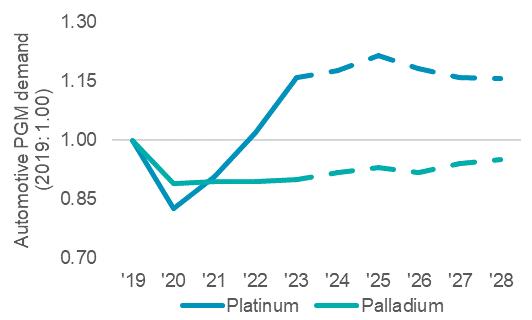

The platinum market transitioned to a deficit of 878 koz in 2023. Strong automotive demand growth from the use of platinum in autocatalysts was a key factor, surging by 16 per cent year-on-year to 3,272 koz. The current trend for platinum to substitute for palladium in gasoline autocatalysts is a significant reason behind the increase in automotive demand (figure 1). In 2023, platinum-for-palladium substitution rose from 391 koz in 2022 to 669 koz. The forecast is for substitution to grow further, reaching 742 koz in 2024.

Figure 1: Since 2019, platinum-for-palladium substitution has supported automotive platinum demand growth relative to palladium

Source: Metals Focus (Pt to 2024) (Pd to 2022), WPIC research thereafter

Platinum and palladium are co-products in polymetallic ores, typically found in association with the other platinum group metals (PGMs). Although there are some physiochemical differences, as part of the PGM group they are similar enough to be interchangeable, to a point, in many applications, and specifically in autocatalysts.

In recent years, platinum-for-palladium substitution has gained traction due to a market – and consequently price – imbalance between platinum and palladium, incentivising automakers to switch to the equally effective, yet less expensive, platinum.

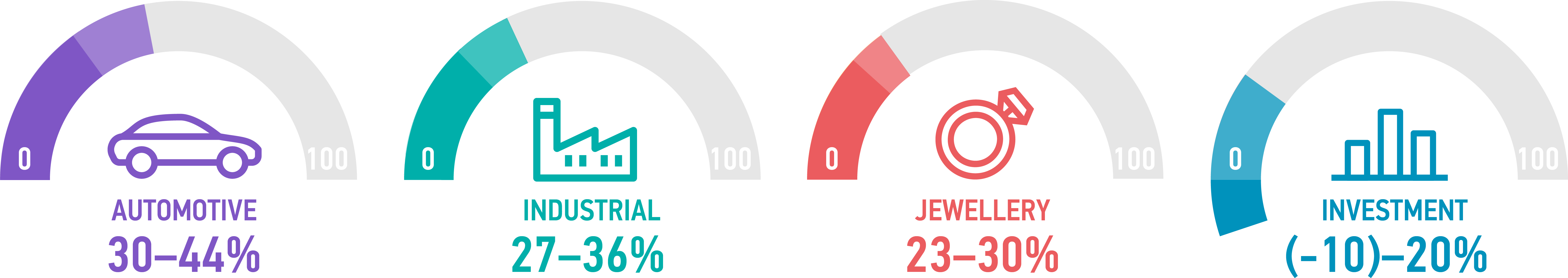

While autocatalysis is a major demand driver for platinum, accounting for around 40 per cent of overall demand, platinum also has a diversity of other end-uses (figure 2), including the developing hydrogen economy. At over 80 per cent, demand for palladium stems predominantly from its use in autocatalysts.

WPIC’s outlook suggests that the platinum market has now entered a period of multi-year deficits, drawing down above ground platinum stocks and tightening markets at a time when the hydrogen economy is accelerating. Conversely, longer term, the palladium market is forecast to turn to surplus from around 2025 as recycling supply increases. This could trigger ‘reverse’ substitution, with palladium substituting for platinum, freeing up platinum for use in the growing hydrogen economy.

Overlaying this dynamic is the recent narrowing of the palladium price premium to platinum. Should palladium begin trading at a discount to platinum, it brings with it the possibility of nearer term reverse substitution occurring. However, existing platinum-for-palladium substitution, including that forecast for 2024, is largely embedded in annual automotive demand due to the certification and manufacturing process (a PGM catalyst is locked in for the lifetime of a vehicle platform, typically for seven years).

Figure 2: Platinum Demand Drivers

Source: WPIC Platinum Quarterly, minimum and maximum ranges over period 2019-2023

How does substitution work?

Being closely grouped transition elements, PGMs have similar physiochemical properties, meaning that to a greater or lesser degree they can perform similar roles in different applications with variable effectiveness. In the case of platinum and palladium used in autocatalysts, platinum catalysts are far less prone to sulphur poisoning, while the use of some palladium in catalysts enhances stability at higher temperatures. With the declining sulphur content of fuels over the past two decades, platinum and palladium in autocatalysts are interchangeable on a 1:1 basis in gasoline vehicles.

To achieve regulatory certification, setting the relative ratio of the PGMs in an autocatalyst occurs during the development of the emissions controls system for the engine of a new vehicle model, or in response to new emissions control limits being imposed.. At this point, those ratios are locked in for the lifetime of that vehicle platform, typically seven years. Even though subsequent price movements might move the economics of the autocatalyst in an unfavourable direction, it is unlikely that redesigning the emissions control system and going through the certification process again will justify the cost or risk, particularly in passenger cars.

WPIC estimates that around 15 per cent of vehicles produced in any given year are new models where substitution during development can easily occur. As a consequence, the ebb and flow of the substitution process plays out over an extended period of time and, for example, the platinum-for-palladium substitution currently underway will be embedded for many years to come.

Why does substitution occur?

Commodity prices are impacted by supply demand/imbalances. In the event of oversupply, the price of a commodity would normally be expected to fall until uneconomic supply is curtailed, or the price falls to a level that attracts new demand into the market. Conversely, in the event of a market being in undersupply, the price of a commodity is normally expected to increase until new supply is attracted to the market, or demand is priced out of the market. The polymetallic nature of PGM bearing orebodies means that there are multiple price inputs establishing the economics of production. Thus, mine supply is unlikely to react to the changing fortunes of any one specific commodity. Primary mine supply is therefore highly (but not totally) price inelastic.

However, the ability to substitute platinum for palladium and vice versa in certain applications helps, to an extent, to balance the market over time, with the automotive sector historically switching between PGMs when market imbalances arise.

Since 2017, when the palladium price began to exceed the platinum price, price differentials and – more latterly – security of supply concerns have driven platinum-for-palladium substitution in emissions control systems.

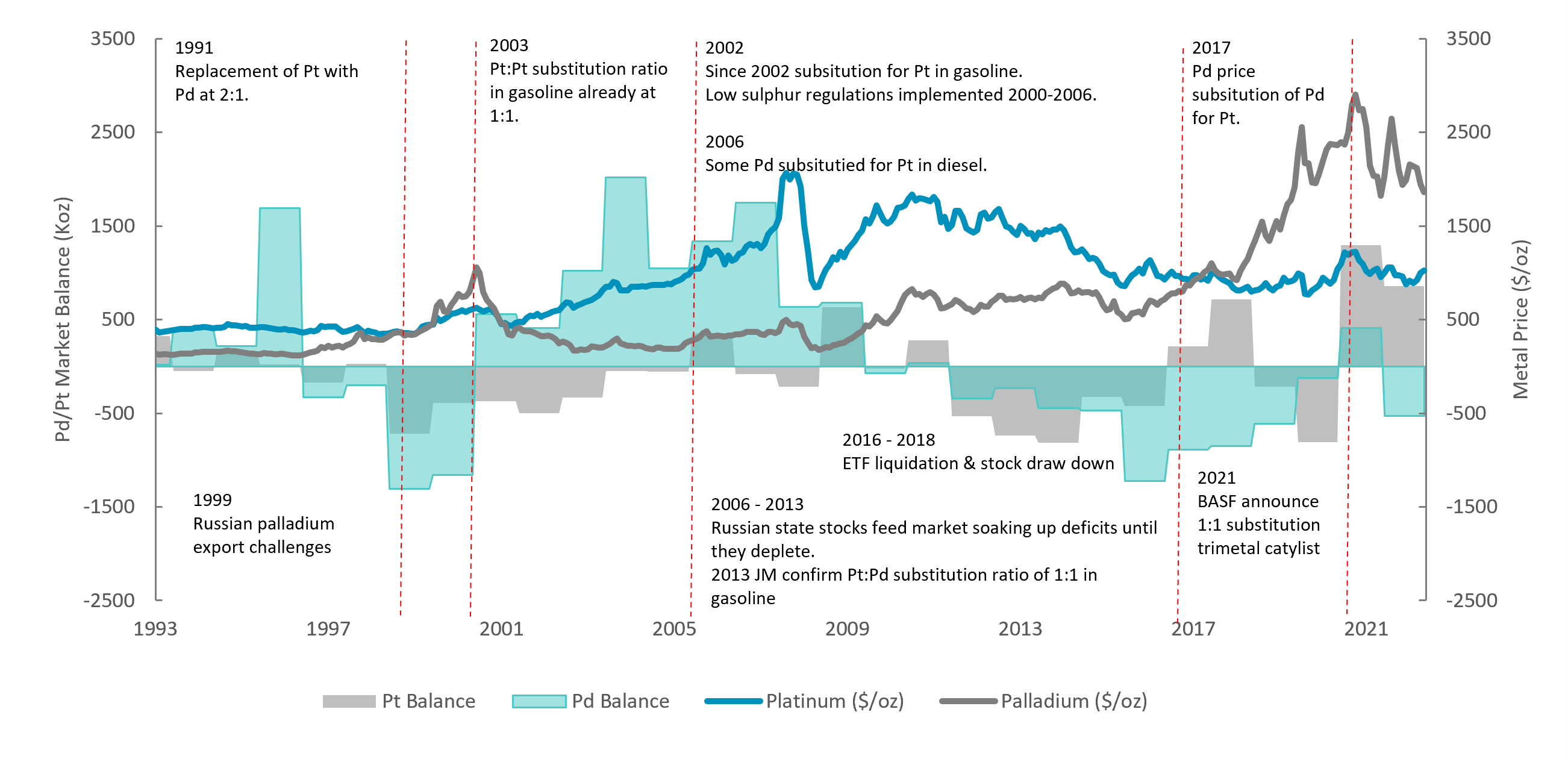

This is not a new phenomenon, with the bidirectional ebb and flow a function of metal availability, security of supply, relative pricing, and catalytic effectiveness (figure 3).

Figure 3: Historic bidirectional substitution between platinum and palladium in gasoline and diesel drivetrains

Source: Bloomberg, Johnson Matthey, Metals Focus, WPIC Research

Outlook for platinum and palladium markets

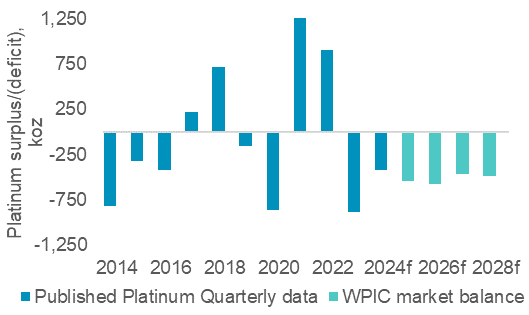

The platinum market entered a period of sustained deficits in 2023, with WPIC supply and demand data demonstrating a deficit of 878 koz for full year 2023, with a second consecutive deficit of 418 koz forecast for 2024. Beyond 2024, WPIC’s most recent Two- to Five-Year Supply/Demand Outlook indicates further platinum market deficits of around 500 koz per annum continuing each year through to 2028 (figure 4).

Figure 4: Platinum deficits through to 2028

Source: SFA (Oxford) from 2014 to 2018, Metals Focus from 2019 to 2024f, Company guidance, WPIC Research from 2025f

Multi-year platinum deficits, exacerbated by ongoing substitution of platinum-for-palladium in automotive end uses (which reached 669 koz in 2023 and is forecast to rise to 742 koz in 2024) will drawdown above ground platinum stocks and tighten markets at a time of rapid acceleration in the growth of the hydrogen economy, and consequent demand growth for platinum in hydrogen-related technologies.

Palladium demand peaked in 2019, following eight successive years of supply deficits. Due to the impact of reduced automotive production during the pandemic, the palladium market swung to surplus in 2020, reverting back to deficits in 2021 and 2022. A palladium market deficit of 600 koz is estimated for 2023.

In WPIC’s current five-year palladium outlook, automotive demand for palladium, which is responsible for some 80 per cent of total palladium demand, grows modestly, rising to a high of around 8,500 koz in 2027. The market deficit eases to 106 koz in 2024 before entering a period of sustained and growing surpluses on the back of a significant growth in recycling supply.

Future substitution trends

Now platinum has entered a period of sustained market deficits, and with palladium forecast to move towards a series of market surpluses from 2025, WPIC expects the platinum-for-palladium substitution trend to gradually slow, and eventually cease, with palladium-for-platinum ‘reverse’ substitution occurring from 2026, depending on the extent and timing of palladium supply-side growth. We should note, however, that while this outlook is predicated on the future market balances of the two metals, it is possible that due to geopolitical tensions some end-users will remain committed to using platinum in order to minimise their exposure to Russia in their supply chain (Russia accounts for about 45 per cent of global palladium mine supply, but only 11 per cent of platinum supply).

The expected palladium-for-platinum reverse substitution will only be in small volumes initially as the substitution process is a lengthy one given it is almost always only conducted on new models and is then locked in for the lifetime of those models, typically seven years. It will therefore take a long time to even unwind the platinum-for-palladium substitution that is currently occurring.

Positively, as palladium is substituted for platinum, it liberates platinum supply to become available for the rapid growth in the hydrogen economy, alleviating concerns that platinum could prove to be a bottleneck in the development of the proton exchange membrane technology that is key to the energy transition.

The research for the period since 2019 attributed to Metals Focus in the publication is © Metals Focus Copyright reserved. All copyright and other intellectual property rights in the data and commentary contained in this report and attributed to Metals Focus, remain the property of Metals Focus, one of our third-party content providers, and no person other than Metals Focus shall be entitled to register any intellectual property rights in that information, or data herein. The analysis, data and other information attributed to Metals Focus reflect Metals Focus’ judgment as of the date of the document and are subject to change without notice. No part of the Metals Focus data or commentary shall be used for the specific purpose of accessing capital markets (fundraising) without the written permission of Metals Focus.

The research for the period prior to 2019 attributed to SFA in the publication is © SFA Copyright reserved.

This publication is not, and should not be construed to be, an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. With this publication, neither the publisher nor its content providers intend to transmit any order for, arrange for, advise on, act as agent in relation to, or otherwise facilitate any transaction involving securities or commodities regardless of whether such are otherwise referenced in it. This publication is not intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and nothing in it should be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any investment or security or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction. Neither the publisher nor its content providers are, or purports to be, a broker-dealer, a registered investment advisor, or otherwise registered under the laws of the United States or the United Kingdom, including under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 or Senior Managers and Certifications Regime or by the Financial Conduct Authority.

This publication is not, and should not be construed to be, personalized investment advice directed to or appropriate for any particular investor. Any investment should be made only after consulting a professional investment advisor. You are solely responsible for determining whether any investment, investment strategy, security or related transaction is appropriate for you based on your investment objectives, financial circumstances, and risk tolerance. You should consult your business, legal, tax or accounting advisors regarding your specific business, legal or tax situation or circumstances.

The information on which this publication is based is believed to be reliable. Nevertheless, neither the publisher nor its content providers can guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information. This publication contains forward-looking statements, including statements regarding expected continual growth of the industry. The publisher and Metals Focus note that statements contained in the publication that look forward in time, which include everything other than historical information, involve risks and uncertainties that may affect actual results and neither the publisher nor its content providers accept any liability whatsoever for any loss or damage suffered by any person in reliance on the information in the publication.

The logos, services marks and trademarks of the World Platinum Investment Council are owned exclusively by it. All other trademarks used in this publication are the property of their respective trademark holders. The publisher is not affiliated, connected, or associated with, and is not sponsored, approved, or originated by, the trademark holders unless otherwise stated. No claim is made by the publisher to any rights in any third-party trademarks.

© 2024 World Platinum Investment Council Limited. All rights reserved. The World Platinum Investment Council name and logo and WPIC are registered trademarks of World Platinum Investment Council Limited. No part of this report may be reproduced or distributed in any manner without attribution to the publisher, The World Platinum Investment Council, and the authors.

Related links

World Platinum Investment Council - WPIC®

World Platinum Investment Council - WPIC®