Insights

BOJ’s tailwinds: inflation, labor crunch and corporate profits

By Tetsuo Harry Ishihara

Recent BOJ comments seem to be preparing the markets for the possibility of Japan’s first rate hike in 17 years, in the form of a liftoff from negative rates. Adding fuel to the fire, a BOJ review of monetary policy since 2013 concludes that they had success in their 30-year fight against deflation. Meanwhile, with inflation above 2 percent and a massively improved output gap, Prime Minister Kishida may be hoping to announce Japan’s “exit from deflation” next year. Market consensus for liftoff appears to be centered around next April to July, after key wage data but before possible rate cuts abroad.

Recent BOJ comments

A string of recent comments from BOJ officials culminated in a strong market reaction on Dec 7. The 10 year yield spiked 10 basis points, and the tail on a 30 year auction could effectively be called the worst on record. Some notable comments from board members include,

“The possibility (of attaining our inflation target) is slowly rising” (Gov. Ueda, Nov 6)

“Japan’s deflationary environment appears to be changing rapidly” (Adachi, Nov 29)

“There are signs that wage growth will soon be higher than inflation” (Nakamura, Nov 30)

“It is very likely that the exit (from unconventional policies) will have positive outcomes such as higher bank profitability and higher interest income for households” (Dep Gov Himino, Dec 6)

“The effects on corporate interest rate burdens will differ but will generally be better compared to past eras of high debt and low cash” (Dep Gov Himino, Dec 6)

“A virtuous wage-price spiral is gradually becoming apparent” (Dep Gov Himino, Dec 6).

“I expect an even more challenging situation to begin towards the end of this year and to continue into next year” (Gov Ueda, Dec 7)

The market moving Ueda comment on Dec 7 was in response to a lawmaker’s question about challenges he has faced so far. However, some interpreted to mean upcoming change at the BOJ meeting on Dec 18-19, and BOJ officials rushed to tone down expectations soon afterwards.

Besides the comments, a Dec 4 BOJ workshop to conduct a review of their unconventional monetary policies since 2013 concluded that they “contributed to the attainment of a non-deflationary situation” according to the Nikkei news on Dec 6. The BOJ also concluded that the policies succeeded in pushing up inflation by about 1 percent, and outstanding loans by about 20 percent.

Three tailwinds for the BOJ

BOJ’s stated goal of attaining 2 percent in stable and sustained inflation supported by wages currently has three tailwinds.

Tailwind 1: the highest inflation in 40 years

Japan’s headline inflation is effectively the highest in 40 years. Removing the effects of massive energy centric subsidies – totaling over 15 trillion yen – headline CPI would be around 4 percent. The main drivers have been food and energy. As Japan imports about 70% of its calories and over 80% of its energy, the sharp weakening of the yen post corona exacerbated the situation.

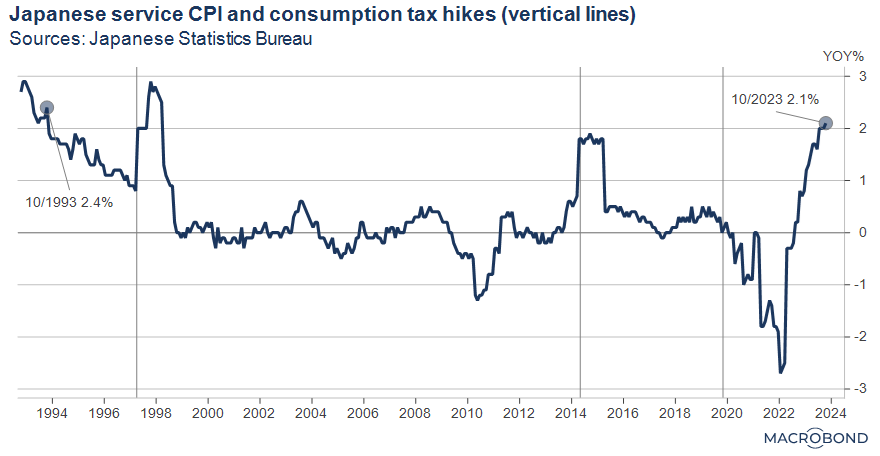

In a positive surprise, services inflation – after hovering near zero for decades – has also risen to the highest level in 30 years excluding consumption tax effects, as the next graph shows. Governor Ueda and former Governor Kuroda have both pointed out the importance of service inflation, which is driven by wage growth, and is less cyclical than goods inflation.

Tailwind 2: a labor crunch

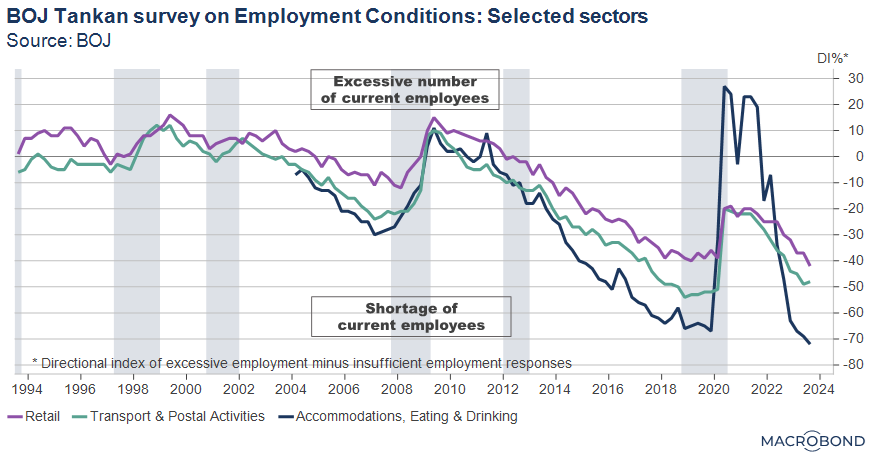

By some measures, Japan’s labor crunch is the worst in about 30 years and the worst among major nations. BOJ’s Tankan survey of about 10,000 firms confirms this, with the Directional Index of Employment Conditions approaching the tightest levels in 30 years for both large and small firms.

On the positive side, the labor crunch contributed to the FY2023 nationwide wage hike noted above. However, on the negative side, it also appears to be getting critical by some aspects. Bankruptcies due to labor shortages in the Jan-Oct period were up 2.4 times from the same period last year, according to Tokyo Shoko data. And in some rural areas, public transportation is being reduced due to a lack of operators, and accommodation/food services are scrambling to cope with the lack of staff in the face of a tourist boom. Some local governments have started programs to hire tourists in return for food and board.

The tightness is widespread, but among the major Tankan reporting sectors, retailers, restaurants, hotels, and couriers appear to be among the most affected, as the next graph implies. Others include healthcare, construction and IT.

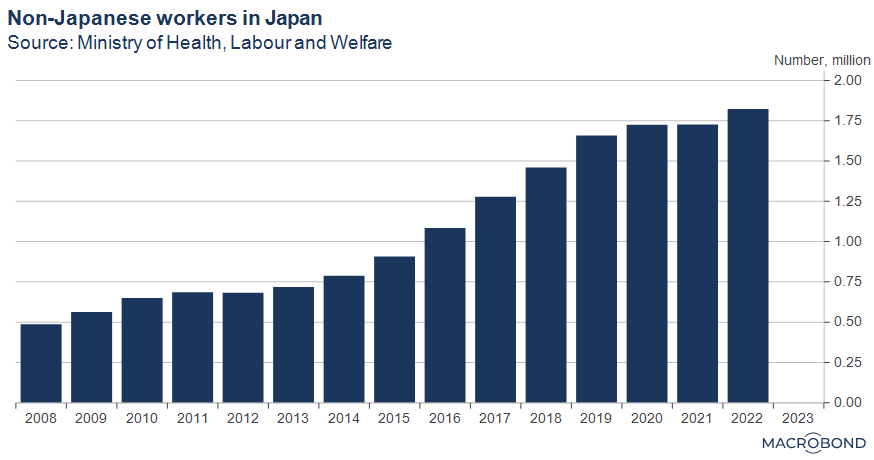

Across industries, tech and self-service is increasing, along with more non-Japanese workers. As the next graph shows, non-Japanese workers have more than tripled since 2008, but the weak yen post-corona has dampened its growth. Higher wages and/or a stronger yen are needed to attract more workers to Japan.

Tailwind 3: corporate profits

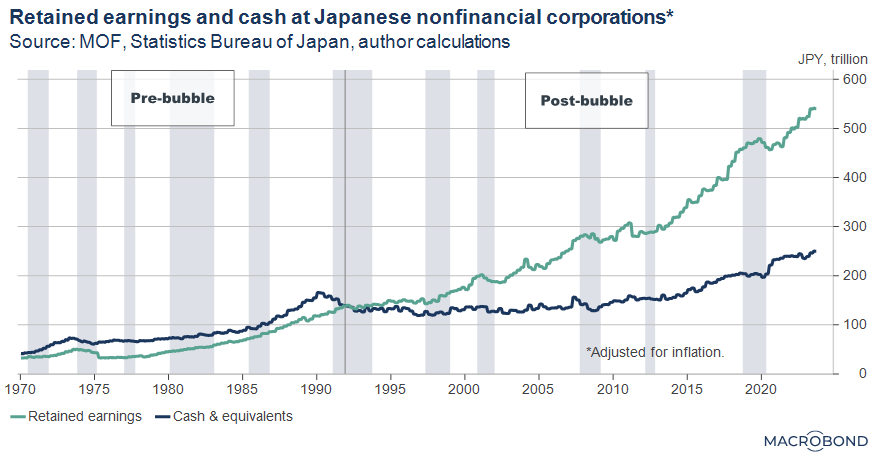

Corporate profits for FY2023 are on track to achieve record levels. Capex could hit a new record, helped by a tech redux led by global semiconductor companies[1] . Retained earnings and cash equivalents are also at record levels, meaning companies have the leeway to make wage hikes[2] .

[1]As we noted in Japan’s inflation revolution, Japan is attracting both domestic and foreign investment to cement its role in global semiconductor supply chains. Examples include investments by Taiwan’s TSMC in Kumamoto, South Korea’s Samsung in Yokohama and America’s Intel in Toyama.

[2]Some critics say that decades of wage repression contributed to those profits. Japan’s consumers have long demanded outstanding service and quality at the lowest possible prices – which often meant repressing wages, especially in the service sector.

Continued wage growth expected

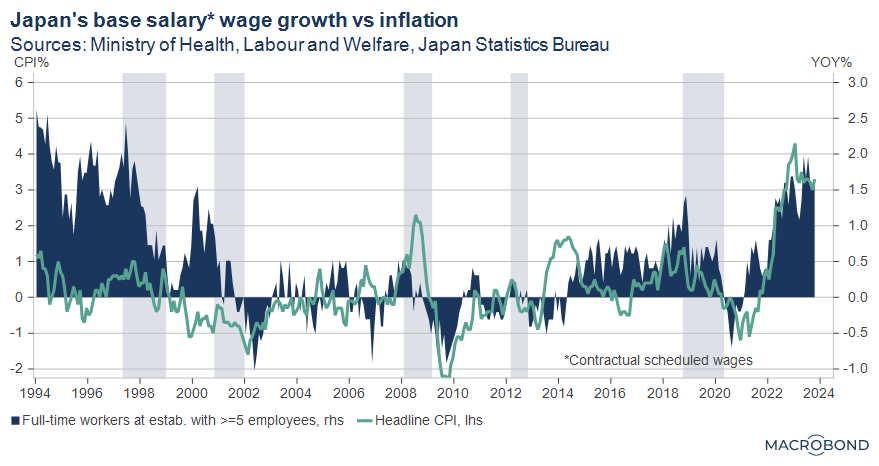

Record inflation was the catalyst for wage hikes this year, as the next graph implies.

Demands from Rengo, the labor organization representing about 5,000 major unions, are the benchmark for national wage negotiations. For FY2023, Rengo ultimately called for “about 5 percent” in total wage growth and attained 3.6 percent – the largest total hike in almost 30 years – including a “base-up” (base salary increase) of 2.1 percent, the largest base-up on record (no specific base-up target was set). For FY2024, they will probably raise the bar to “5 percent or higher” including a specific base-up target of “3 percent or higher”.

Strong wage growth is expected to continue in FY2024, and Rengo results should start to appear in late March. The BOJ has highlighted those results as being key for upcoming decisions, and they are also conducting their own wage surveys. Positive signs of wage growth are apparent, and the practice of forward wage guidance continues to expand. Recently, some major firms in the food and beverage industry and in the financial industry announced their intentions to hike wages by 7 percent to 15 percent next year.

Timing and other implications

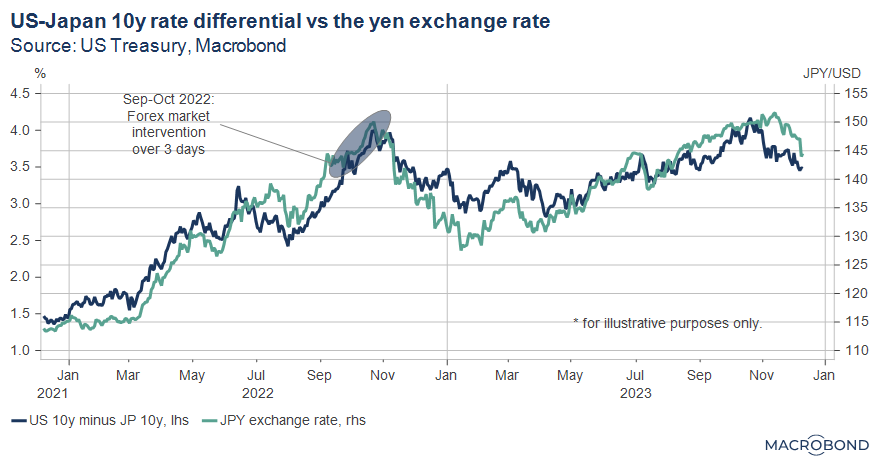

Liftoff’s effect on the yen – which drives equity prices – remains a concern. Some politicians fret it could cause a sharp slowdown led by a stronger yen. However, even if liftoff occurs, a healthy US-Japan interest rate differential should continue, supporting the dollar and preventing any excessive yen strength. Japanese investor flows into US equity markets could also stem the tide.

Politics is another driver of market expectations. PM Kishida’s massive 17 trillion yen (113 billion US dollar) economic package has a stated goal of ending deflation. Wage growth is a pillar, as well as individual tax cuts worth 40,000 yen per person next June. With inflation above 2 percent and a massive improvement in Japan’s output gap, he may announce a historic “exit from deflation” around that time.

A BOJ liftoff from NIRP (negative interest rate policy) would be Japan’s first rate hike in seventeen years if it occurs. Many say it is long overdue, with even the conservative regional banking industry calling for it. At the moment, the consensus seems to be centered around the April to July period, after the key Rengo data in March but ahead of possible rate cuts abroad.

Related links