Insights

Is the yen’s weakness more structural now?

Written by Harry Ishihara, Macro Strategist

Japan has been reporting record current account surpluses which in theory should generate demand for the yen. However, the yen continues to stay weak giving rise to hypotheses about its structural weaknesses. The debate has implications for the Japanese economy, monetary policy, and stocks.

Components of the current account

The current account for Japan consists of the trade balance, the primary income balance, and the secondary income balance. The trade balance reflects the difference between exports and imports. The primary income balance reflects net flows in interest, dividends and reinvested earnings that are generated from direct (e.g., factories) and financial investments. Finally, the secondary income balance reflects transfers that receive nothing in return, such as grants. Note that in this post, we will use the terms “primary income” and “primary income balance” interchangeably.

Karakama’s hypothesis

A current account surplus is usually driven by a positive trade balance, which in turn provides demand for the yen as foreign currency revenues from exports get converted. Thus, Japan’s large current account surplus should in theory offset the weakening due to the widened US-Japan interest rate differential.

However, the yen has remained weak, which supports the stock market but drives inflation higher. Various hypotheses about its STRUCTURAL weakness are gaining traction in Japan, led by Mizuho Bank’s Chief Market Economist, Daisuke Karakama. His thinking has recently been presented to the Ministry of Finance, which oversees Japan’s currency policy[i].

Sea Change

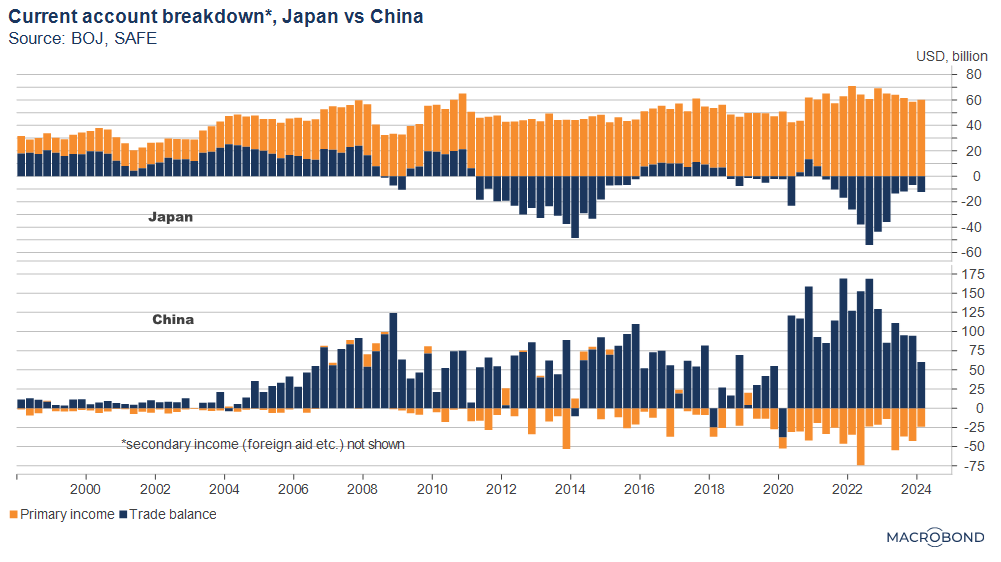

As the first graph shows, Japan’s current account is no longer being driven by the trade balance, but by a record primary income balance – basically the net[ii] dividends, interest and reinvested earnings from foreign direct investment (FDI) and financial investments such as bonds, stocks and loans. Meanwhile, for the past decade or so, the trade surplus has become a trade deficit, making Japan look more like a holding company of overseas assets than an exporter.

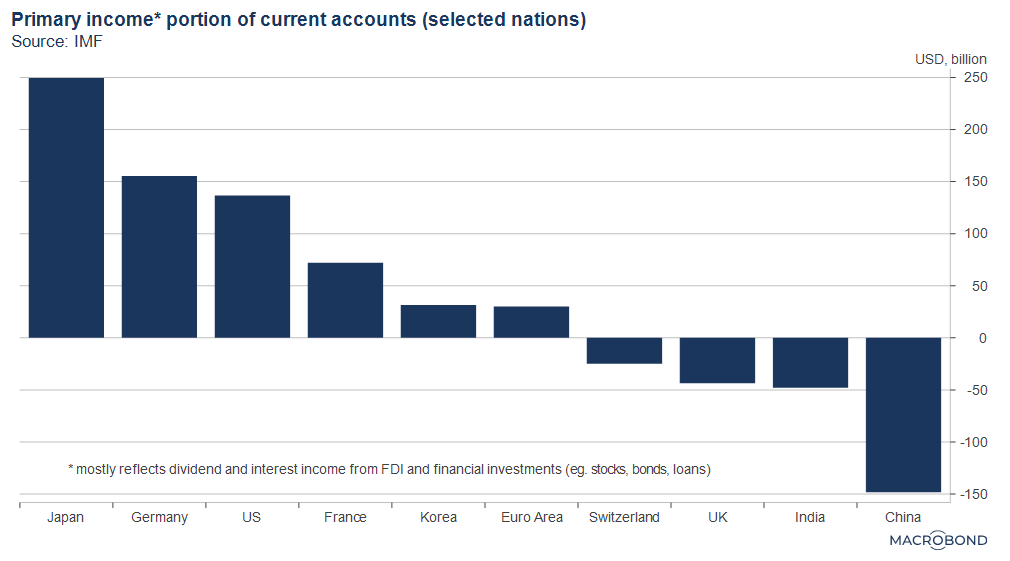

The contrast to China’s current account in the bottom half of the graph is also stunning. In most countries, the current account is driven by the trade balance like China’s, not the primary income balance like Japan’s. Compared to other nations, Japan’s primary income balance appears to be unusually large as the next graph shows.

Primary Income Drivers

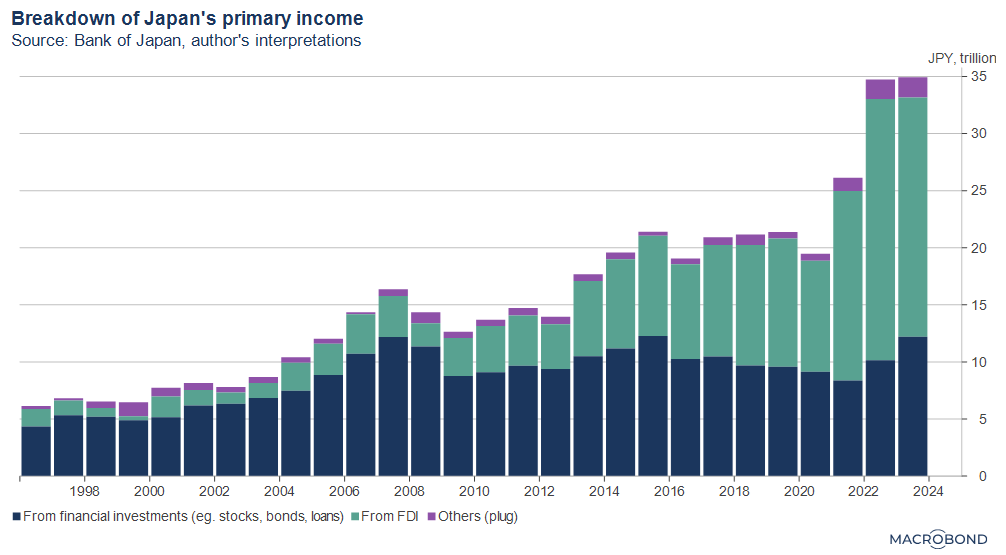

The driver of primary income has also changed. As the next graph shows, until about 10 years ago, Japan’s primary income had been driven by flows generated from financial investments. However, since then, the flows generated by FDI have surged, helped by a weak yen.

What is driving FDI? According to the BOJ (Quarterly Review, Aug 2023), Japanese companies led by the automobile sector have increasingly shifted production, sales and even exporting functions abroad from about 2014 onwards. And for many years, some components of the current account are positively correlated with overseas automobile production.

Reasons for the yen’s structural weakness

If the current account is reporting record surpluses, should that not cause the yen to strengthen more? Perhaps not, for 4 reasons[iii] that look more structural than transitory:

- Interest rates. A wider interest rate differential with the US has been an obvious driver of the weaker yen. However, it could remain wide, supported by sticky US inflation. Going forward, a possible Donald Trump presidency could also be inflationary via sweeping tariffs, changes to immigration policies and tax cuts. According to former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, “There has never been a presidential platform so self-evidently inflationary as the one put forward by President Trump”[iv].

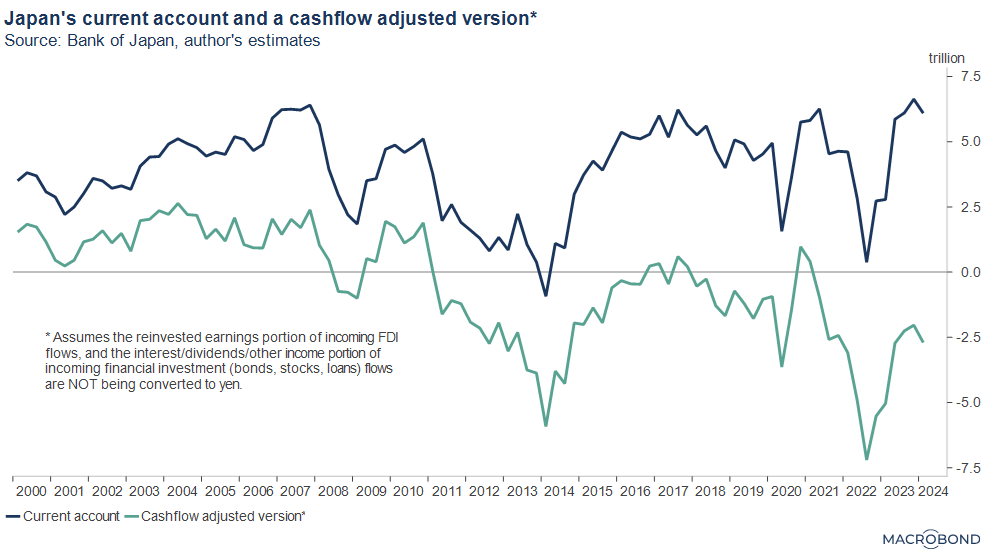

- The Karakama Hypothesis The structure of Japan’s current account could mean that the yen remains weak, as much of the primary income’s dividends, interest and reinvested earnings from abroad will NOT get converted into the yen and instead get REINVESTED abroad, according to Karakama. Based on Karakama’s logic[v], we made a “cashflow adjusted” version of Japan’s current account, which shows a large DEFICIT instead of a surplus (green line in the following graph). Deficits weaken demand for the yen.

- NISA expansion. Tax free NISA (Nippon Individual Savings Account) investment accounts have been expanded since January 2024, increasing flows to Japanese stocks (about 45% of the Jan-April total) and US and other markets abroad. The changes expanded both the “growth” account for individual stocks and investment funds and the “tsumitate” or installment account (ie. dollar-cost averaging) for periodic investments into investment funds. The expansion not only supports the Karakama hypothesis, it could also mean that there will be more periodic automated selling of the yen to purchase US stocks under the installment accounts. This selling will likely be insensitive to market fluctuations.

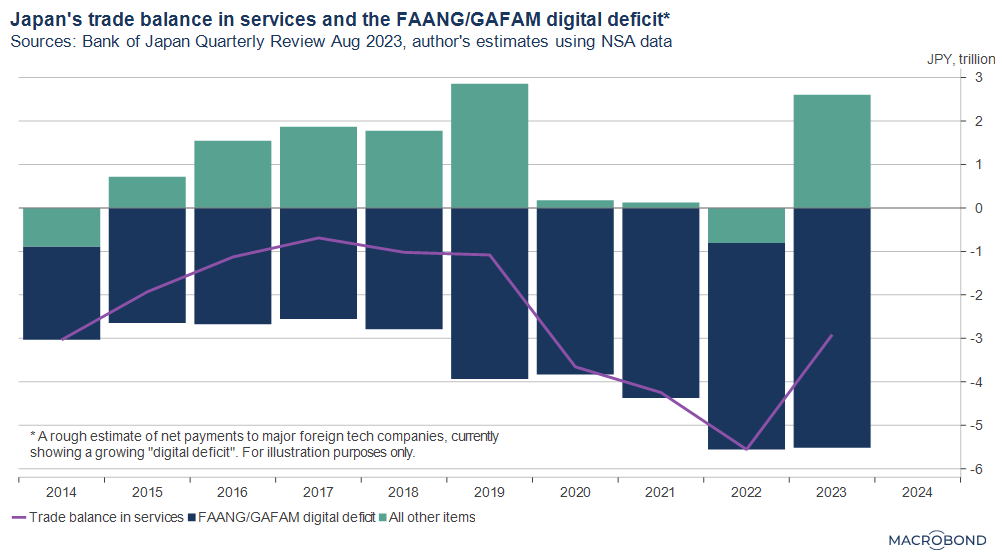

- FAANG/GAFAM Digital Deficit. A fourth reason for a weak yen is the “digital deficit” theory reported in the BOJ’s Quarterly Review dated August 2023. In the following graph, the blue bars show the “FAANG/GAFAM digital deficit” almost dominating Japan’s trade balance in services. It is reportedly driven by the fees paid to major tech companies for online ads, subscriptions, software, cloud storage, apps, music and other services.

Conclusion

The yen may have become structurally weakened for four reasons: 1) the US-Japan rate differential, 2) the Karakama hypothesis about incoming flows getting reinvested abroad and not converted to the yen, 3) automated selling of the yen for NISA installment accounts, and 4) the huge “FAANG digital deficit”.

A structurally weak yen could lead to a more hawkish BOJ as it could drive inflation via imported food and energy, and eventually boost wage growth. At the same time, it would provide a tailwind for Japanese stocks and tourism.

[i] https://www.mof.go.jp/policy/international_policy/councils/bop/outline/20240326_3.pdf (Japanese)

[ii] Here “net” means the difference between incoming and outgoing flows

[iii] Some of these were discussed at a MOF meeting in March 2024: https://www.mof.go.jp/policy/international_policy/councils/bop/outline/20240326_1.pdf (Japanese)

[iv] https://www.afr.com/world/north-america/president-trump-would-unleash-inflation-across-america-20240605-p5jjel

[v] In this Reuters post, Karakama explains that most reinvested earnings from FDI as well as the dividends and interest from financial investments will probably NOT be converted into the yen: https://jp.reuters.com/opinion/forex-forum/HWYKMWCUMBPMLH2C4SP5H3TZAI-2024-02-20/ (Japanese)

Related links